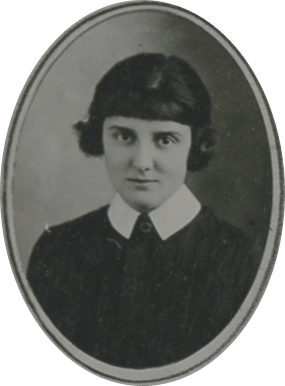

Ida Pitt was a relatively short woman, one of those adults against whom growing youth like to measure their height; yet she was a worthy yardstick by which to assess one’s adulthood and Christian maturity. She came to Winnipeg in 1922 at the age of 25, a deaconess recently graduated from the Methodist National Training School for Christian Workers (in Toronto). A young woman from small-town Ontario, she came to the western city of Winnipeg, to an area populated by recent immigrants, to an area that reported the highest rate of juvenile delinquency in that city. And she came to a congregation that didn’t want her. It was a tough way to begin. [photo to the left is Ida in 1924, wearing her deaconess uniform and pin]

In 1921, the Rev. J.M. Shaver had come from Thunder Bay to Winnipeg to be the superintendent of All Peoples’ Mission. At that time, the Methodist Church decided to reorganize MacLean Mission, making it part of All Peoples’ along with Stella and Sutherland Missions. The process by which that was done was without consultation and many of the people at MacLean were unhappy with the new arrangement. They were particularly unhappy that their minister, Mr. Lee, who had been moved by the Mission Board to another posting. They wished failure on the new superintendent. One of the people who was in the middle of that ill-will was Miss Collinson, the MacLean Mission deaconess. She refused to co-operate with Mr. Atkinson, the boys’ worker, and neglected the girls’ work. She was disruptive to the peace and harmony of the mission, gathering a group of dissidents around herself.[1]

In June of the next year, Shaver wrote to Principal Hiram Hull at the National Training School to inform him that he had talked the matter over with Miss Collinson and the Deaconess Aid Society, and was asking that Miss Collinson be replaced. He asked Hull to provide someone “with good common sense and up to date methods”. He got what he asked for in Ida Pitt. At the end of her first year, he reported:

“Miss Ida Pitt, our Deaconess at MacLean Mission, had no small task on her young shoulders when she came to set up girls’ work there, for that district gives the Juvenile Court more candidates than any other district in the City. On the other hand the atmosphere of the Mission was not congenial to girls’ work, for even the girls felt that they had little sympathy from many who held positions on the Official Board. In spite of all these difficulties and the added fact that this is Miss Pitt’s first year on a field, she has made a wonderful success of the work.”[2]

At the end of the second year, Shaver wrote to Winnifred Thomas, the superintendent of the Department of Deaconess Work to say:

“Miss Pitt has proved herself a most capable Girls’ Worker, and good all round Deaconess. She took on her work two years ago under the most trying circumstances, and facing such opposition from people who should have been giving her support. She not only made the work a success, but has won the friendship of those who were formerly opposed to her. In fact, I think I gave her what I would consider the hardest task I ever gave a Deaconess and she has made abundantly good.”[3]

The Annual Report of All Peoples’ for 1922-23 lists the groups whom she had organized and with whom she worked: the Senior Girls (age 14 and over), the children of the Mothers’ Club, five Junior and Intermediate groups, a group called the Sunshine Club for children 6 to 9, another group called the Happy Hustlers, Mission Band, the Senior Girls Sunday School class and a worship service for youth. In total, she was working with 134 children and young people. An example of her success was the president of the C.G.I.T., a girl who “at the beginning caused Miss Pitt no end of trouble” but was now, at the end of the first year, her eager assistant and colleague.[4]

Ida Pitt herself had trouble seeing how much she had accomplished. “I cannot see that I have accomplished anything except to become acquainted,” she wrote during that year. She then went on to tell about some girls who had not come out for groups in the past. “They will never come out,” she was told. During her first weeks at MacLean, she set out to get to know those girls as well as possible, and a week before the group was to begin she went to them and told them that they were needed. By that simple method, she had new, active members.[5]

Letting people know that they were needed was certainly part of the secret of her success. Her second strength was that she visited. She liked visiting. It was a way to get to know people and understand the homes from which her girls came. As the years went on, visiting was always a part of what Ida Pitt did. In 1936 she undertook to call on every home associated with Stella Mission at least twice during the year. Fifteen years later, while at St. Andrews (Elgin Ave.), she reported 876 visits made. In a memorial written after her death in 1963, a friend from Augustine Church wrote:

“When Miss Pitt was at Augustine, she had her finger on the pulse of the whole district. Everyone who was sick, shut-in, or in trouble, be it financial or family trouble, she was right there to give help, encouragement, anything, in whatever line it was needed. She could call practically everyone by name and knew their joys and their sorrows. Night after night she boarded a bus to calI on people who worked during the day and she felt they needed her help and encouragement. It didn’t matter to her whether her work-day lasted ten or more hours, as long as she felt she was doing something to help someone. Unselfishness was her outstanding characteristic.”[6]

An old friend from her youth, from her home town of Shanly, said: “Ida was always helping and doing for others, from a very young age, and it just seemed natural for her to make that her life’s work.”

Growing up in a religious home, her parents led the family in daily prayers and Bible reading, as well as hosting occasional prayer meetings in the home. For many years, Ida’s father was superintendent of the Shanly Sunday School. When Ida was four years old, her mother died, leaving her and a brother and sister with their father, alone on the farm. The brother and sister died in 1909. When her father remarried and a second family came along, it fell to Ida to help raise four young brothers. That delayed her education somewhat, though only temporarily.[7]

In 1920, she enrolled in the (Methodist) National Training School. Here she received an education that undertook to meet three requirements as set out in the Year Book of the Deaconess Society:

1) The Systematic and Comprehensive Study of the English Bible. This is fundamental. Thorough knowledge of the Word of God to the utmost of one’s capacity is the one thing essential for any and every kind of Christian work, and it is the special aim of the School to impart this knowledge.

2) The promotion of Personal Spiritual Life. Spiritual perception and the ability “to teach others also” are necessary to an intelligent understanding and right interpretation of the Word of God. We can only speak confidently and convincingly of “that we do know”. It is important also to promote the personal knowledge of fellowship with Christ, and to be endued with power from on high in order to give efficient and effective service.

3) Practical and Scriptural Methods of Christian Work. The School appreciates the importance of thorough training in this regard, and affords every opportunity to visit the various missions of the city where benevolent and charitable, and also social and settlement work is being carried on.[8]

It was an intensive course of study over two years, covering the areas of Bible, Philosophy of the Christian Religion, History and Missions, Religious Education, Sociology and Social service, Homiletics and Evangelism, Expression (which included public speaking, singing, physical culture and deportment), and Household Science (sewing, first aid, and dietetics). Based on the number of hours assigned to each course, dietetics and sociology were at least as important as courses in the prophets, the teaching of Jesus and the letters of Paul. The compulsory reading lists are perhaps instructive, with Harry Emerson Fosdick being the only author to be read in both years; his The Meaning of Prayer in first year, and The Meaning of Faith in second year.

Ida Pitt brought out of her background and education a theology of walking in the footsteps of the master. In 1934 she wrote,

“My vision is Jesus, some twenty centuries ago, traveling among and working with people. He approached the people through their thinking, interests and positions in life. By his strong personality, high ideals, and loyal faith, His triumphant life won people to him.”[9]

Her objective was to provide a fourfold program, incorporating physical, intellectual, spiritual and social elements. Certainly the spiritual was never forgotten. There was always time to talk about a verse of scripture, to memorize a psalm, or tell a story with a moral. Consistently, the highlights of the group programs were the occasions on which the C.G.I.T. or some other group was responsible for the leadership in public worship. This for Ida Pitt was the purpose of their life together, that they should be conscious of the presence of God and joined together in worship.

However, given the circumstances in which the children of All Peoples’ Mission were living, there was more to be done than just Bible study and worship. It came almost as a surprise to her that they also needed to learn to play. “The girls have always said they had a lovely time at the parties, but I could not understand,” she wrote. “They have shown me another opening. They need guidance and to be shown how to play just as much as they need to be taught how to pray.” Consequently, she organized physical fitness drills and set up basketball leagues. One mother thanked Miss Pitt for the change that had occurred in her daughter. Before going to the Mission, she had seemed to lack interest in anyone or anything. Now she was more alive. Ida Pitt attributed that in part to the involvement in the whole program but specifically to getting into the sports program at the Mission.’[10]

The sports program in the 1920’s and 30’s was something of which All Peoples’ Mission was justifiably proud. J.M. Shaver was convinced that good sportsmanship and a desire for excellence on the field would produce the same outcomes in life. By the end of the 20’s, All Peoples’ Mission was training some of the top athletes in the city, and indeed the country. Their track teams, coached by Slaw Rebchuk, won national championships in 1924 and ’25, Manitoba championships in ’25 and ’27, and Peter Dobush and Kasmer Jastremsky were individual national champions in 1923, ’24 and ’25. The girls may not have been doing quite as well, but they were winning city basketball championships in 1924 and ’26. It was an exciting place to be.[11]

But, sports was probably not Ida Pitt’s strong suit. Throughout her life she had an interest in handcrafts and took courses in everything from paper flower making, to lamp shade decoration, to copper tooling, to leather craft. It was her hope that sometime she could “help the girls to use taste in decorating”, that they would “some day decide they can make their homes more attractive.” There were people who, years later, believed that part of the taste and attractiveness of homes in the northend of Winnipeg could be directly attributed to Ida Pitt and others like her who taught that that mattered.[12] She was anxious to make her girls, foursquare girls.

For the first several years, All Peoples’ Mission understood itself to be a house for all people. Services and groups were open to everyone and, although there was a Sunday School, there was a rather loose sense of denominational definition. There were regularly girls in C.G.I.T. groups whose families were members of the Catholic Church, but who involved themselves at the Mission because their own church did not have such programs. At the end of the 20’s and moving into the 1930’s the Mission began to be criticized by the rest of the United Church for its lack of standards. That was probably an unfair attack as annual reports regularly point out among the people in C.G.I.T. groups, the people on sports teams, and the people attending programs, those who were also members of the Sunday School, or teaching Sunday School, or part of a Bible study. Consistent with the Methodist background of the Mission, reports on the volunteer leadership indicate that none of them smoked or drank.

At any rate, in the 1930’s All Peoples’ Mission made a move to become more formally a church. A space was set aside for use as a sanctuary complete with a pulpit. The sacraments were celebrated and people were confirmed as members. The decision that had the most direct impact on Ida Pitt was a decision that groups like C.G.I.T. should be closed to girls who did not attend Sunday School. Ida Pitt had mixed feelings about that. She loved her girls and felt badly when they dropped out of her groups. Contact with them was a life and death matter. She told the story in 1929 of one girl who stayed away most of the year and then came back saying, “I thought I wanted to be a flapper but always I thought of C.G.I.T. and was not happy.”[13] She found that the older girls were coming to her to talk, “anxious they are to know that they are in their right places, which they can best fill in this world.” The sentence may not be well constructed, but the mood is clear. “The challenge to the Leader is stronger than ever before in my experience for the best and vital things in life,” she wrote.[14]

Consequently, when she writes in 1931, “The C.G.I.T. is strictly the Sunday School classes, no exceptions being made for anyone,” there is some pain in that. “All those girls who find it impossible to come to Sunday School or who are not interested in it are in special groups. The special group is still small too as many a girl expects if she hangs out long enough she will get her own way sooner or later.” Then she added, “I hope to have the old girls all back in one place or the other very soon and some new ones.” Her fellowship with these girls, as well as the boys and adults with whom she associated was important to her. These people were her family.

Although she never married, the church provided her with her family. A few months before her death in 1963, the “boys” (now thirty years older) of All Peoples’ Mission held a party to thank her and honour her. It was these same “boys” who carried her coffin for that was the respect they owed to a woman who had loved them as her children. They may have grown taller than Ida Pitt, but few of them would have said they were bigger.

This profile was written by Peter Douglas, a chapter in his STM Thesis,

A Family Photo of The United Church of Canada Winnipeg, 1930 University of Winnipeg, 1990. (

Click here for printable copy.) Used with permission.

[1] Letter from J.M. Shaver to Hiram Hull, National Training School; June 28, 1922. A copy of the letter is located in the United Church Archives -Winnipeg; All People’s Mission box.

[2] J.M. Shaver, “Report of Deaconess Work in All People’s Mission and McLean House, 1922-23”. United Church Archives -Winnipeg.

[3] J.M. Shaver, letter to Winnifred Thomas, Superintendent of the Department of Deaconess Work, May 1, 1924. United Church Archives -Winnipeg.

[4] Shaver, “Report of Deaconess Work … 1922-23”.

[5] Ida Pitt, “A week with Girls of Maclean”, a report for 1922-23. United Church Archives -Winnipeg.

[6] a) Ida Pitt’s affirmation that she likes visiting is found in “A week with Girls of Maclean”. b) In her “report of the Girls’ and Young Peoples’ Work of Stella Mission for 1935” (written January 14, 1936) she says: “During the year I try to call twice on every home for two main reasons; first to know the mother and father if possible and let them know me. And try to understand better the child’s behaviour.” c) Ida Pitt, “Report from the Deaconess”, Annual Report of St. Andrews (Elgin Ave.) Church, 1951. United Church Archives -Winnipeg, St. Andrews Church box. d) “A Eulogy in Memory of Miss Ida Pitt”, unsigned.

[7] Howard Pitt, letters to Peter Douglas from Ida Pitt’s brother, October 25, 1986 and January 22, 1987.

[8] Yearbook of the Deaconess Society of the Methodist Church, 1921-22. 28.

[9] Ida Pitt, “My Aim and Vision of Work”, written in 1934. United Church Archives – Winnipeg.

[10] Ida Pitt, “A week with Girls of MacLeans”

[11] Photo Album of J.M. Shaver. Property of Jack Shaver.

[12] Ida Pitt, “A week with Girls of MacLean”.

[13] Ida Pitt, “Girls’ Work -Stella Avenue -1929”. United Church Archives -Winnipeg.

[14] Ida Pitt, “Girls’ Work -Stella Avenue -1931”. United Church Archives -Winnipeg.